- August 29, 2020

- Posted by: Aviral Goenka

- Category: DEFENSE & SECURITY, Featured, GLOBAL GOVERNANCE & POLITICS, INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, Latest Work, OPINION

China under President Xi Jinping is risking imperial overstretch with post-pandemic aggression as the premier seeks to press China’s advantage in the region amidst the heightened rate of coronavirus contagion in neighbouring countries. While China’s neighbours are facing the crucial challenges of flattening the epidemic curve and ensuring quick economic recovery, the former has opened multiple fronts in the pursuit of regional, and eventually global hegemony – from Hong-Kong and Taiwan to the South China Sea to the Himalayan frontier. The internationally paralysing pandemic has reinvigorated Xi-Jinping’s efforts to achieve his dream of Chinese glory under the communist rule. Moreover, the premier has diverted international attention from China’s role in the emanation of the pandemic to his imperialistic policies in the region as it is endeavouring to extend its influence in Middle-East Asia by forging an alliance with Iran. Reports suggest that China and Iran are entering a 25-year strategic partnership in trade, politics, culture and security that will embolden Tehran’s crippling economy and regional strength and allow Beijing to extend its strategic foothold.

Retrospectively, China and Middle-Eastern countries have had strategic partnerships, however, what differentiates this curveball of development from others is that both China and Iran have regional and international ambitions, and have adversarial relationships with America and their neighbours. The security component of the deal might have implications for the balance of power in the continent, particularly for the US and its allies such as Israel and Saudi Arabia in the Middle-East and India in South-Asia. Moreover, the Chinese interests and growing influence in East Asia and Africa collides with American goals which have increased the plausibility of a proxy-confrontation in the Middle-East as Beijing can look to counter the US hegemony through Iran. Furthermore, this cooperation poses a new challenge for the Indian foreign and defence policy as it finds itself in a strategic bind in an increasingly hostile region. The consequences and implications of the agreement are far-reaching as it operates on the internal, regional and international level.

The report acquired by the New York Times detailed the Sino-Iranian agreement which would dramatically expand Chinese presence in banking, telecommunications, ports, railways and dozens of other projects. Iran will supply a regular and discounted supply of Iranian oil over the next 25 years and the two nations will strengthen military cooperation through joint training and exercises, joint research and weapons development and intelligence sharing. This will allow China to establish its stronghold in the region that has been a strategic preoccupation and a crucial component of the US foreign policy. The alliance which was proposed by Xi Jinping during a visit to Iran in 2016 — was accepted by President Hassan Rouhani’s cabinet in June 2020, but remains to be ratified by the Iranian parliament. It can be argued with conviction that if the deal comes into effect as detailed in the report, the burgeoning partnership will exacerbate hostilities in the deteriorating Sino-American relations.

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi (R) shakes hands with Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif during their meeting at the Diaoyutai State Guest House in Beijing on December 31, 2019. Photo: Getty Images

President Donald Trump’s aggressive policies which were aimed at isolating Iran has pushed it towards China, as Beijing included Tehran in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) [that seeks to create a web of connectivity across Europe, Asia, and Africa] and decided to invest $400 billion in Iran’s oil and gas, infrastructure and transportation sectors. As a result, the influx of these gigantic sums in Iran’s economy and infrastructure posed a challenge to American interests in the region and the world, as China continuously seeks to expand its reach around the globe. Iran is not an exception to this imperialistic aggression; Tehran might perceive this development as an opportunity to rehabilitate itself in the global community and rekindle its economy but they could merely be a subject of China’s debt-trap-diplomacy. The communist regime employs debt and the subsequent pressure to trap low-income countries, particularly through the means of BRI. The argument is simple, China promises humongous investments that countries cannot turn down, consequently leverages the debt to secure strategically important infrastructure. For example, Beijing used this strategy in Sri-Lanka to acquire a port and in Djibouti to access a port and military installations. Tehran does need a friend, but China can prove to be a dangerous one.

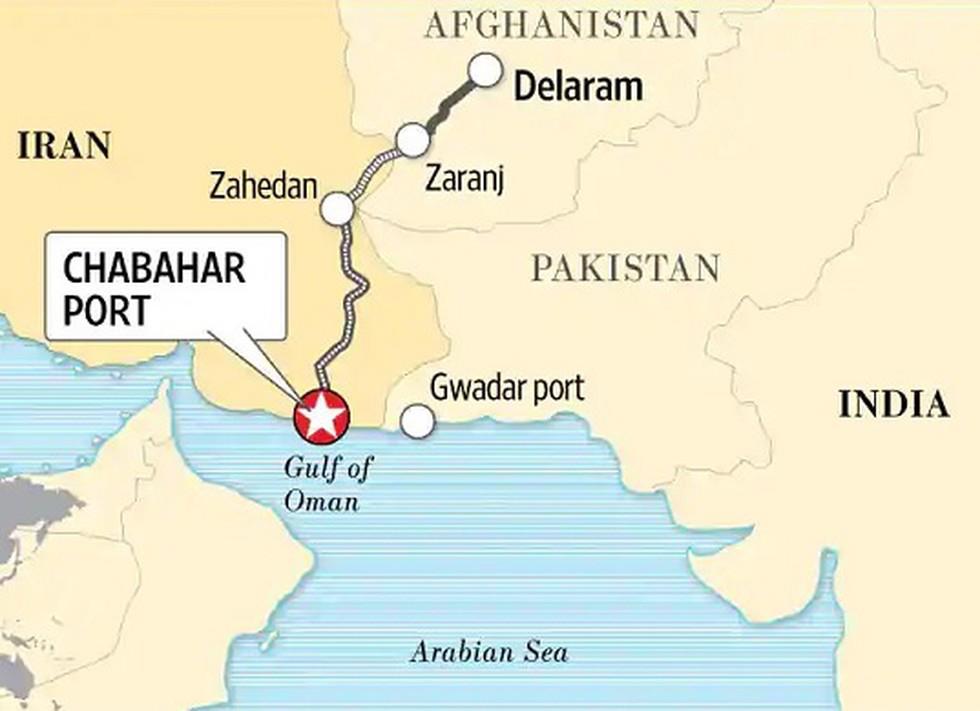

Chinese policymakers deserve credit for recognising Iran as a key player in the region and as an alternative route to secure itself against the US-led military action in Asia. However, from the Indian perspective, this strategic development is alarming as it threatens its position and security in the region. The probable consolidation of a China-Pakistan-Iran nexus will isolate India in the region amidst continuous border rifts with its two neighbouring adversaries; growing hostility from KP Sharma Oli’s regime in Nepal; the resurgence of Taliban’s political power in Afghanistan; Chinese exploitation of Indo-Bangladesh relations. Besides the strategic bind, the direct impact of Chinese investments in Iran has resulted in the exclusion of New Delhi from Chahbahar rail project which was envisaged to act as a bridge between India, Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia, bypassing Pakistan. Indian narratives around the project highlight the vitality of the project in countering the growing Chinese influence in the region, particularly the Gwadar port in Pakistan which was constructed and controlled by China under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) design. Despite India’s continuous emphasis on the exclusivity of this project, Tehran has tried to leverage Beijing and Islamabad to invest in the Chabahar Special Economic Zone. While recent reports suggest that Iran will proceed with the project unilaterally, this economic partnership can result in the infusion of Chinese money in the project, which will effectively allow China unfettered access to the Gulf of Oman through the seaport in Chabahar.

Chabahar-Zahedan Rail Project

Chabahar-Zahedan Rail Project

For India, the implications are more grave than the loss of a commercial deal. The ground is extremely precarious as Beijing can be expected to mitigate tensions between Islamabad and Tehran, consequently, distancing New Delhi. Moreover, this deal will allow China to integrate Gwadar and Chabahar seaport [the distance between them is merely 172 km] and gain an additional strategic edge in case of a maritime confrontation with India and Western powers in Asia.

The vulnerable position of India can be attributed to the geopolitical rift between Washington and Beijing which will only get more intricate with the tussle over Iran. Over the past years, India has faced the challenge of balancing its relations with Iran and the US and has only implemented United Nations-mandated sanctions on Iran. However, after continuous pressure from the Trump administration to block the import of Iranian oil, India caved in. The sanctions did not derail the Chabahar project but severely impeded the construction process. Consequently, Indo-Iranian bilateral relations deteriorated as the latter perceived the transformation of India’s foreign policy as the approach has become Washington-centric. New Delhi’s policies towards Iran are balancing on its strategic and economic interests in the region as Iran has the potential to allow India to expand its status beyond the continent and assume a great power rank. Besides granting access to Central Asia, Tehran could have been instrumental in reducing Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan and countering the Chinese expansion. However, what was once the magnum opus for India to improve its position has now been pushed away by geopolitical forces, particularly Trump’s aggressive stance towards Iran and this new strategic partnership with China.

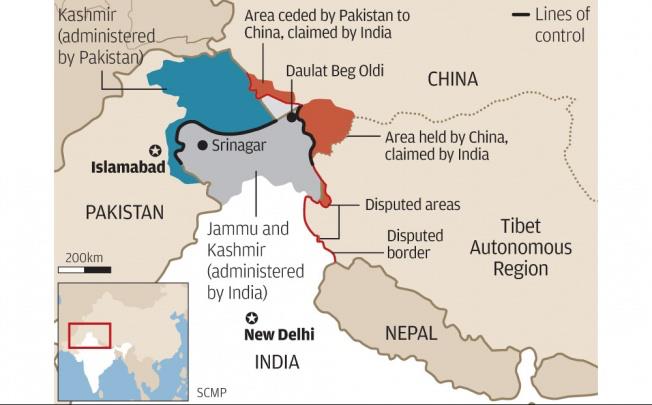

While it is clear that Trump’s sanctions and marginalisation drew Iran closer to China and shook the bedrock for Indian interests in the region, it is more important than ever for New Delhi to preserve its relations with Washington. The recent clashes between India and China over Galwan Valley have disturbed the improving bilateral relations as the Ministry of External Affairs of India claimed that Beijing attempted to unilaterally change status quo. In this hostile geopolitical climate, the emergence of this potential alliance and improved Chinese access to the Indian Ocean it is imperative for India to secure itself by solidifying its relations with Washington. In spite of this necessary alliance with the US, New Delhi will have to hedge between the former and its ally in Eurasia, Russia.

It can be argued that Russia will join its historical ally, Iran to form a tripartite alliance with China, but reports from Moscow suggest that the leadership have observed a significant change in Chinese diplomacy, particularly in wake of the pandemic. China and Russia have excelled in finding common ground and mitigating differences, but the emergence of an excessively confrontational, aggressive and risk-loving foreign policy of Beijing has alarmed Moscow. Russia believes that the Chinese attitude has the potential to drive a wedge between Russia and third countries such as India. Russia would not want to disturb the strategic partnership with India as the latter remains Russia’s largest market for arms (56% of the Indian weapons share comes from Russian markets). Moreover, Russia has played a crucial role in subduing Sino-Indian tensions, for example, Moscow organised a trilateral meeting between the foreign ministers of Russia, India and China to solve the Ladakh territory dispute peacefully. Albeit the Chinese aggression in the region is coercing India to focus on Washington, India cannot give up its ties with Russia. With the exceeding isolation in the region; geographical proximity and historical ties make Russia a necessary ally and subsequently the cornerstone of the Indian grand strategy in Asia.

Photo: Financial Times

Besides bilateral alliances with Washington and Moscow, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), a forum of four maritime democracies—India, US, Japan and Australia — can prove to be pivotal in balancing the Chinese influence in South and Middle East Asia. The Quad has attained strategic significance in the past as the four nations converged towards this partnership due to China’s aggressive and imperialistic policies. Retrospectively, New Delhi was hesitant over its involvement in the Quad and pursued a policy of cautious hedging over China, however, strategic concerns about Beijing’s expansion which undermines India’s great power aspirations and continuous encouragement of Pakistani insurgency in Kashmir Valley have pushed the former to acknowledge its position in the Quad. By and large, despite the initial criticism of this partnership, China’s misinformation campaigns, aggressive posturing in Taiwan, Hong-Kong and East and South China seas, and the unilateral endeavours to alter international borders have manifested the utility of enhanced cooperation between the four countries. Furthermore, with the heightened US-China rivalry the Quad is showing signs of transforming into a military alliance, albeit an informal one.

From a realist perspective, the deterioration of bilateral relations between Tehran and New Delhi could be ascribed to India’s shift towards the US, increased criticism of India’s role in Jammu and Kashmir and the treatment of Muslim minorities and the impediment to the Chabahar rail project due to American sanctions. The strategic proposals of a partnership with China could be Tehran’s signals to pressure India to multi-dimensionalise economic relations and minimise the impact of “third party influence.” As Iran pivots towards the East, it acknowledges the necessity of foreign investments; however, the strategic partnership still needs approval from the Iranian parliament and Tehran’s politicians have raised their concerns over the influx of Chinese money in the country –- former president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has been a skeptic of the deal. Additionally, Tehran will seek to maximise its leverage and freedom of action rather than play second fiddle to a rising hegemon. Additionally, India’s dilemma depends on the results of the upcoming US elections — If Joe Biden comes to power, America’s approach towards Iran might be less aggressive, however, in case of Trump’s reelection sanctions will be inevitable.

The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of PCI, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent.

Lovely blog! I am loving it!! Will come back again. I am bookmarking your feeds also. Jilli Tremaine Germain

Good post! We are linking to this particularly great content on our website. Keep up the great writing. Simone Orville Wendel

Superb, what a webpage it is! This blog provides helpful information to us, keep it up. Colline Renaldo Domenic

You completed certain fine points there. I did a search on the theme and found the majority of people will have the same opinion with your blog. Dotty Ernie Coltson

I love it whenever people get together and share ideas. Great website, continue the good work. Katalin Cart Jaquiss

Fabulous, what a weblog it is! This webpage provides useful information to us, keep it up. Alejandra Alanson Rodrick

This paragraph will assist the internet viewers for setting up new blog or even a weblog from start to end. Lauraine Jedediah Mercie

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this article plus the rest of the website is also really good. Myrtice Emmery Rakia

Excellent post. I will be dealing with a few of these issues as well.. Maybelle Scottie Eliason

As the admin of this web page is working, no uncertainty very soon it will be famous, due to its quality contents. Lurline Regan Ankney

Enjoyed every bit of your blog. Much thanks again. Fantastic. Sallee Ingra Noella

I was looking through some of your blog posts on this website and I believe this web site is rattling informative ! Keep on putting up. Sophronia Burton Lebna