- June 25, 2020

- Posted by: Mukul Bhatia

- Category: DEFENSE & SECURITY, Featured, GLOBAL GOVERNANCE & POLITICS, Latest Work, OPINION

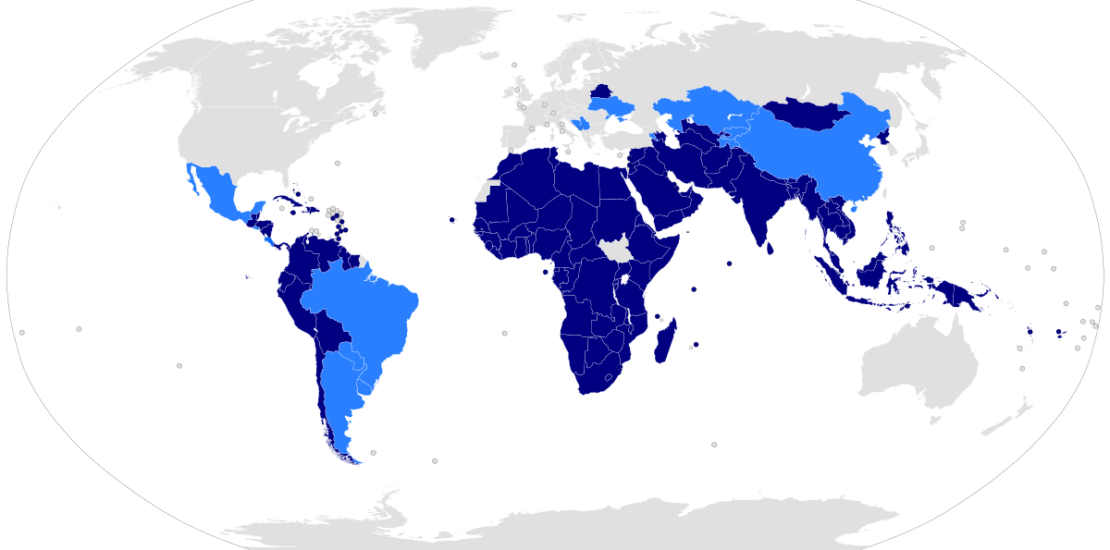

On 4th May, 2020, PM Modi participated in the online Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit, where he claimed that NAM has ‘often been the moral force of the world’ (Modi, 2020). While asserting the importance of NAM in a world ravaged by the Covid-19 pandemic, he called for a ‘new template of globalization based on fairness, equality and humanity’ (Modi, 2020). Modi’s participation in the summit came as a surprise due to his absence from the 17th and 18th NAM summit held in Venezuela and Azerbaijan respectively, a move that signaled his departure from Nehruvian foreign policy. This departure was seen as justifiable, citing reasons such as the complexity of challenges that India faces today, particularly with respect to China and incompatibility of NAM’s anti-West orientation with an increasingly interdependent world. However, the perceived relevance of the NAM would depend on the world view of the actors and its relation with the empirical. There is, thus, merit in analyzing these specific world views, before abandoning the NAM as a policy instrument for the developing world.

With its roots in the 1955 Bandung Conference of Asian and African states and formalized during the first conference of the non-aligned states that took place in Belgrade in 1961, the NAM was conceived as a paradigm of international relations in which newly independent states could assert their agency in the face of binaries created by the Cold War. And while today these binaries have faded away, and the neoliberal model of economics has prevailed, the principles of the NAM have not lost their validity. The purposes and principles laid out in the conference at Belgrade (Ministry of External Affairs, 2012) symbolize ideals worth striving for in order to establish an international system based on justice, equality and cooperation. The complex interdependencies of the globalized world have not exterminated the possibility of furthering strategic interests of states through domination and control.

With its initial focus on the problem of colonialism and the process of decolonization in the aftermath of the Second World War, the NAM soon turned its head towards the preservation of sovereignty for the Third World, necessitated by expansionist ideology of the superpowers during the Cold War. The ‘positive’ or ‘constructive’ neutrality (Singh, 2009) gave the states an ideological space to maneuver on the international stage in a way that could support their domestic state building projects. The NAM’s appeal was rooted in the experience of Suez crisis, the possibility of self-serving intrusions, and potential Zionist aggression for the Arab world; Africa’s need for warding off foreign powers and aiding the African National Liberation Movements; Influence exercised by the United States in the Latin American theatre (Ghosh, 2019). Thus, the thrust of the movement was to prevent the Global South from being reduced to ‘spheres of influence’ by the Global North. Even though scholars have contested the salience of binaries such as East and West, North and South in the contemporary world and consequently NAM’s validity (Pant, 2016), the behavioral logic that such classifications entail has hardly lost its application. A glaring example of this is the growing influence of China in Africa. Following the 2000 Ministerial Conference of Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), China, incentivized by the prospect of capturing consumer markets and resources such as oil, has sought to forge a global partnership with the African nations (Lee, 2010). Many observers in the West have expressed concern over China’s perception of Africa as a region ‘up for grabs’ (Lee, 2010). More recently, the Chinese infrastructural investments in Africa under the One Belt, One Road Initiative have been analyzed through a similar lens. The service and repayment of credit extended by China to finance projects such as East African Railway Master Plan, can significantly impede the ability of the African states to invest in other development projects at home, and can compel them to make payments in-kind, paving the way for natural resource extraction akin to what was carried out by European colonists (Su, 2017).

Another case is that of Sri Lanka where there is a competition among China, US, India and Japan in order to gain strategic control over the Indian Ocean theatre (Bandarage, 2020). The neocolonial aspirations can be discerned by the acquisition of the Hambantota Port over a controversial 99-year lease and investment in the Colombo International Financial City built on land reclaimed from the Indian Ocean by China; the Indian development of the Trincomalee oil-tank farm; Indo-Japanese partnership for the construction of container terminal at the Colombo port; the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) proposed by the US, that has been an object of widespread opposition in Sri Lanka (Bandarage, 2020) (Pararajasingham, 2019) (Safi, 2018).

At the same time, Britain’s current involvement in Africa can be interpreted as a continuation of its neocolonial ambitions. The description of Britain’s renewed control over Africa’s key mineral resources through its companies as ‘new colonial invasion’ by a 2016 report published by the War on Want is a case in point (Shah, 2020). So is the use of ‘High Level Prosperity Partnerships’ scheme of 2013 that sought to provide a number of African states access to British expertise in financial services and education in order to secure access to raw materials for British oil and mining companies (Shah, 2020).

Thus, the world that we inhabit today is controlled by a plurality of state actors, operating on the identity spectrum between power aspirant and developing nation. However, the means employed by them to gain control seem to continue across specific power configurations. A case for NAM’s perpetuation is supported by this world view. The anxiety associated with neocolonialism, that much of the developing world, continues to experience is built into the fabric of the movement. Ahmad Sukarno’s assertion that ‘colonialism has also its modern dress, in the form of economic and intellectual control, and actual control’ made at the 1955 Bandung Conference (Timossi, 2015), still resonates with the experience of the developing states in trying to navigate the complexities of the international system. The calls made at the Lusaka Summit in 1970, for the revision of the global economic structure with a focus on self-reliance owing to a collective disdain for neocolonialism (Ghosh, 2019), can be revisited in a new light as the world reaps the bittersweet dividends of globalization. The constructive role played by the movement, in bringing the issues that plagued the developing world into the mainstream, must continue to inform global agenda. Issues such as poverty, underdevelopment, environmental degradation, that form a part of the NAM agenda, continue to persist and have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 Pandemic.

Despite its significance, the NAM has experienced waning support from its proponent states. Its lack of a robust institutional setup is often seen as a hindrance to the adoption of an action-oriented approach towards issues. However, the quasi-institutional form that NAM operates in has allowed it to function without bureaucratic control (Ministry of External Affairs, 2012). Moreover, action through a reformed United Nations to achieve internationally agreed development goals has always been a major part of the NAM agenda (Strydom, 2007). The Third World solidarity that emerged at the UNCTAD in 1964 that enabled the developing states to place their agenda successfully at the international forum has often been attributed to the moral force of the NAM (Jain & Chacko, 2009). Other efforts such as the calls for cooperation in the field of information and media made during the debates around the New World Information and Communication Order (NWICO) during the 1970s and the 1980s became the basis of UNESCO’s International Programme for the Development of Communication (IPDC) and the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) (Padovani & Nordenstreng, 2005). Thus, the NAM can continue to act as an international pressure group, and foster a dialectical process in international relations in order to curb the effects of unfettered globalization. NAM’s ability to operationalize critical discourse and become a platform for launching an inclusive growth paradigm, has also been highlighted by its engagement with women’s issues (through its Ministerial Meeting on Woman and Empowerment, held in Cuba in 2005, for example) (Jain & Chacko, 2009).

There is still currently a need to enhance the NAM’s ability to act as a support system for developing nations to voice their concerns over the nature of the prevailing international system. The absence of a permanent secretariat has often been cited as a reason for NAM’s limited success (Keethaponcalan, 2016). Additionally, notwithstanding the importance of enhancing the role of civil society organizations for furthering the agenda of the movement, the NAM has predominantly remained a statist affair. There is a need for establishing formal institutional channels for participation of civil society organizations in the movement. Finally, there is a need for a streamlined policy-oriented approach to addressing issue areas and overseeing the implementation of its recommendations, and lending a sense of procedural and substantive continuity to the movement.

Bibliography

- Bandarage, A. (2020, June 29). Neocolonialism and geopolitical rivalry in Sri Lanka. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from Asia Times: https://asiatimes.com/2020/01/neocolonialism-and-geopolitical-rivalry-in-sri-lanka/

- Ghosh, P. (2019). Non-Aligned Movement. In P. Ghosh, International Relations (Fourth Edition) (pp. 169,170). New Delhi: PHI Learning Private Limited.

- Jain, D., & Chacko, S. (2009). Walking Together: The Journey of the Non-Aligned Movement and the Women’s Movement. Development in Practice, Vol. 19, No. 7, 895-905.

- Keethaponcalan, S. I. (2016). Reshaping the NonAligned Movement: Challenges and Vision. Keethaponcalan Bandung J of Global South, 3:4.

- Lee, C. J. (2010). Between a Moment and an Era: The Origins and Afterlives of Bandung. In C. J. Lee, Making a World after Empire: THE BANDUNG MOMENT AND ITS POLITICAL AFTERLIVES (pp. 1, 2). Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Ministry of External Affairs. (2012, August 22). History and Evolution of Non-Aligned Movement. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from Ministry of External Affairs: https://mea.gov.in/in-focus-article.htm?20349/History+and+Evolution+of+NonAligned+Movement

- Modi, N. (2020). PM Modi addresses virtual Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) Summit | PMO. Non-Aligned Movement Virtual Summit . Prime Minister’s Office, Government of India.

- Padovani, C., & Nordenstreng, K. (2005). From NWICO to WSIS: another world information and communication order?: Introduction. Global Media and Communication, 1(3), 264–272.

- Pant, H. V. (2016, September 29). End of the Road for the Non-Aligned Movement? Retrieved June 19, 2020, from Yale Global Online: https://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/end-road-non-aligned-movement

- Pararajasingham, A. (2019, August 02). US Push for New Military Agreement Runs Into Fierce Opposition in Sri Lanka. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from The Diplomat: https://thediplomat.com/2019/08/us-push-for-new-military-agreement-runs-into-fierce-opposition-in-sri-lanka/

- Safi, M. (2018, August 02). Sri Lanka’s ‘new Dubai’: will Chinese-built city suck the life out of Colombo? Retrieved June 19, 2020, from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/aug/02/sri-lanka-new-dubai-chinese-city-colombo

- Shah, R. (2020, April 23). A Western Delusion: Narratives Surrounding Neocolonialism in Africa. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from Oxford Political Review: https://oxfordpoliticalreview.com/2020/04/23/a-western-delusion-narratives-surrounding-neocolonialism-in-africa/

- Singh, S. (2009). NAM IN THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD ORDER : An Analysis. The Indian Journal of Political Science, 70(4), 1213-1226.

- Strydom, H. (2007). The Non-Aligned Movement and the Reform of International Relations. Max Planck Yearbook of United Nations Law, Volume 11, 1-46.

- Su, X. (2017, June 09). Why Chinese Infrastructure Loans in Africa Represent a Brand-New Type of Neocolonialism. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from The Diplomat: https://thediplomat.com/2017/06/why-chinese-infrastructural-loans-in-africa-represent-in-brand-new-type-of-neocolonialism/

- Timossi, A. J. (2015, May 15). REVISITING THE 1955 BANDUNG ASIAN-AFRICAN CONFERENCE AND ITS LEGACY. Retrieved June 19, 2020, from The South Centre: https://www.southcentre.int/question/revisiting-the-1955-bandung-asian-african-conference-and-its-legacy/

The views expressed in this paper are the views of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of PCI, its Board of Directors, or the governments they represent.